I read ‘The Diary of Anne Frank’ as a young teenager and, like many other readers of the novel, discovered not a gritty tale of Holocaust hardship but a vibrant young girl dealing with the trials of approaching adulthood like every young teenager before her.

I read ‘The Diary of Anne Frank’ as a young teenager and, like many other readers of the novel, discovered not a gritty tale of Holocaust hardship but a vibrant young girl dealing with the trials of approaching adulthood like every young teenager before her.

But Anne Frank was not like every other teenage girl.

Born into a Jewish family in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam, Frank’s father, Otto, saw the threat towards the Jews early enough to put his family into hiding. Using the warehouse of his business on Prinsengracht, Otto converted the upper floors, and relocated to a life under cover in the ‘Secret Annex’. With tremendous alacrity he sacrificed the comfort of his own family, increasing the risk of noise and thus safety, to share an already tiny space with the Van Pels family and another man.

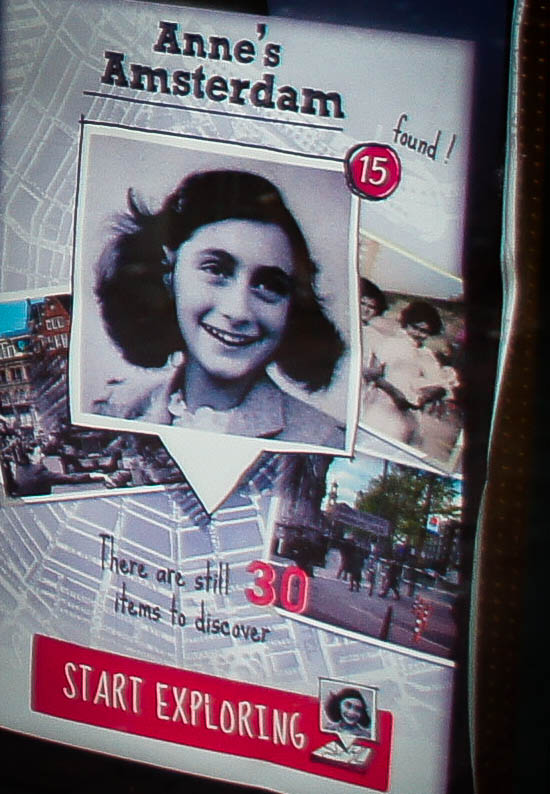

As the Anne Frank museum is one of Amsterdam’s most popular tourist attractions, I was warned that the queues would be long and advised to pre-book. Being rather disorganised by nature I forgot, but as luck would have it the queue only consisted of 10 people when I arrived at 11.30 on a rainy December morning. Most people in Amsterdam seemed to be preoccupied by their Christmas shopping instead.

Visitors to the museum are able to wander around at leisure and read the information on display, which includes detailed accounts of the warehouse, biographies of both families, and excerpts from Anne’s diary. Looped video clips show interviews with Otto Frank, neighbours of the family, Anne’s classmates – including an ex-boyfriend of sorts, and survivors from the Camps. The bookcase that swings open to reveal the secret passageway, and the posters that Anne glued to the walls of her room, still exist.

Disappointingly, the Annexe has been stripped of all the furniture and belongings, leaving a series of empty rooms that certainly seem larger than they would have to Anne and the other inhabitants. It is very difficult to get a true sense of the lack of space experienced by the families—who were unable to move around by day, or turn lights on by night, for fear of getting caught.

The loft area, the only place in the Annexe where the inhabitants could get a glimpse of the outside world, is closed to visitors.

Unless you have read Anne’s diary, it is difficult to feel a connection with her from the museum. That is not to say that the museum is not interesting—certainly it is. But the museum alone is not enough to convey what she went through.

Perhaps the lack of furniture makes it seem too sterile, too empty, too soulless?

Perhaps the trail of tourists winding their way from room to room, some disrespectfully laughing loudly at each other, distract from the reality of the place?

[mks_boxquote align=”right” width=”250″ arrow=”0″]“It is the silence that frightens me so in the evenings and at night…I can’t tell you how oppressive it is never to be able to go outdoors, also I am very afraid that we will be discovered and be shot.”

–Anne Frank, The Diary of a Young Girl[/mks_boxquote]Or perhaps Anne’s own words are the only medium powerful enough to truly convey the relentless fear, the anguish of vanquished ambition, the long hours of crushing boredom, and the soul-destroying lack of hope that descended on her in her darkest moments in the Annexe?

It’s not that I wasn’t moved by the museum. More that I wasn’t as moved as I expected to be. Maybe, after a while, travellers become desensitised to this type of tourism?

As I exited the museum, stepping out into the brisk cold mist of a late December day, I took a deep breath of clear, free air, and scanned my surroundings. The house is in an attractive neighbourhood of Amsterdam, sitting alongside a picturesque canal, and flanked by equally grand town houses I wondered if any of the neighbours had known the Frank family. Had they seen Anne playing in the street as a young girl, or coming to meet her father at work?

How had she been betrayed? Had somebody heard a noise? Seen a candle in an upper window? Suspected that the family once living around the corner had not really disappeared at all, but were hiding in the upper echelons of a warehouse, desperately praying each day that the World would see sense and end their terrible plight?

Were they betrayed by a neighbour? Somebody who lived in the innocent-looking houses nearby? Who made the call that brought the Gestapo running, and forced the Frank family into camps, never to return?

Did that person watch from behind the curtains as doors were broken down with rifles, as families were torn apart, and hope was obliterated?

And if they did—if it was a cowardly neighbour—then where are they now?

It was then, standing outside the museum and taking in the houses on either side, that I realised I had indeed been moved.

How do you respond to so-called ‘dark tourism’? Do we need these places to exist in order to understand, or does keeping them hold us back from moving on? Have you ever been moved, or not moved, by a place that you have visited?

I read the book after visiting the house. Since visiting the house, as well as Berlin, I have become so fascinated with this period. I’m planning on visiting Auschwitz when im in Krakow next month also.

John recently posted..The Islands of Toronto

I am also fascinated by this period, and it’s really interesting to explore it from all angles, especially coming from Britain as I do. I have never visited Auschwitz, but hope to do so. Apparently it is worth making the trip to Bergen-Belsen too. It will be a harrowing experience, to be sure, but I really feel that these places are important to visit. I look forward to hearing what you think of it!